The following article is from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader.

Here’s something to think about next time you open a box of crayons. We take it for granted that the pigments used to color our clothes, dishes, and art supplies are clean and safe— but as these colors of the past reveal, that’s not necessarily so.

(Image credit: Zubro)

(Image credit: Zubro)

Color: Mummy Brown

Made From: Actual mummies

How Did That Become a Thing? Long before there were art stores, the most reliable source of powdered chemicals of all kinds was the apothecary. Europeans had gotten it into their heads that Egyptian mummies were powerful medicine, and from the 1300s to the early 20th century, ground mummies were prescribed for everything from headaches to gout to epilepsy. Adventurous artists discovered that when mixed with oil paint, powdered flesh from mummies made an excellent light brown color. It was used extensively from the 1700s into the mid-1920s.

True Colors: Despite the belief that mummies were indestructible, it turned out that flesh in paint tended to shrink and crack with time. But the thing that really doomed Mummy Brown was the dwindling supply of mummies. By 1964, it was officially as dead as a pharaoh; an article in Time magazine quoted a representative of a major art supply house as saying, “We may still have a few limbs lying around somewhere, but not enough to make any more paint.”

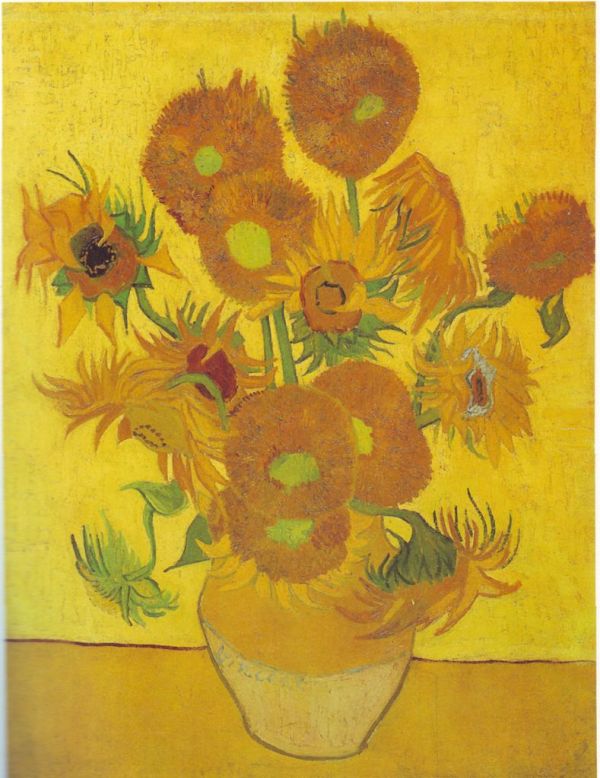

Color: Chrome Yellow

Made From: Lead chromate

How Did That Become a Thing? In the 1790s, French chemist Nicolas Vauquelin identified a new element in the mineral lead chromate, which had been discovered 35 years earlier in Siberian caves. The new element, dubbed “chromium,” was used to make a rich yellow paint that covered other colors in one coat. It was not only bright— it was also cheap to make, leading it to become a favorite of Vincent van Gogh. Unfortunately, van Gogh had a peculiar habit: he liked to nibble on his paints. In fact, he liked Chrome Yellow so much that he once emptied a tube of it into his mouth. Many of the symptoms of insanity the artist exhibited, including the halos around lights that appeared in his paintings, can be caused or exacerbated by heavy metal poisoning.

True Colors: Unfortunately, Chrome Yellow was not only toxic but also unstable. When exposed to sunlight, it tended to fade and turn brown or green; exposure to sulfur (an ingredient in some paints) hastened that process. In fact, many of van Gogh’s paintings have been affected. Although artists can still buy leaded paints, Chrome Yellow has been largely supplanted by the safer, more permanent Cadmium Yellow.

(Image credit: H. Zell)

(Image credit: H. Zell)

Color: Royal Purple

Made From: Sea snails

How Did That Become a Thing? When Cleopatra became fond of a very expensive purple dye, she started a long tradition. The color was expensive because making it was difficult and unpleasant. You started by crushing the mucus out of 250,000 sea snails (known as the spiny dye murex) and soaking it for weeks in stale urine. Worse, a quarter million snails could make only half an ounce of dye— enough to color a single toga, a piece of tapestry, or a ceremonial flag or two. The stench was so bad that dyers were required to do their work far outside the city walls. The nauseating smell clung to them even after washing; in fact, the Talmud granted an automatic divorce to women whose husbands became dyers. Yet all that trouble and expense —and even the smell— only made it more attractive to those who wanted to show off their money and power.

True Colors: You’d think that overharvesting of that sea snail would kill the dye. It didn’t. Neither did the horrible stench that clung to the fabric. The hue remained a status symbol worn by the royal and the wealthy for many centuries. And it might still be stinking up the place if an 18-year-old chemist named William Perkin hadn’t accidentally invented the first synthetic dye in 1856. The color of Perkin’s dye was a rich purple he called “mauve.” It was also inexpensive, which made it accessible to almost anybody… and that’s what killed Royal Purple.

(Image credit: Chris Goulet)

(Image credit: Chris Goulet)

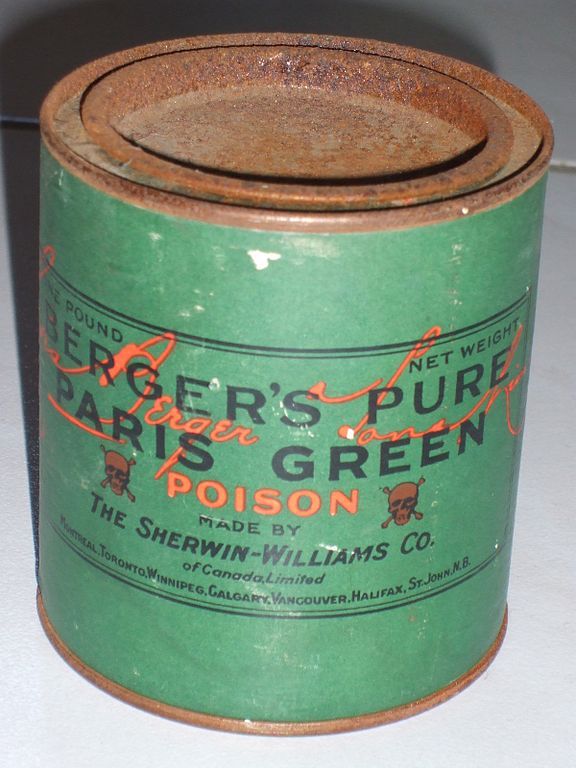

Color: Emerald Green/Paris Green

Active Ingredient: Arsenic

How Did That Become a Thing? Until 1775, green paint was commonly made from copper carbonate— the rust you see on copper building trim and the Statue of Liberty. That year Carl Scheele, the brilliant Swedish chemist who discovered chlorine, invented a beautifully bright green pigment from an arsenic compound. He called it Scheele’s Green, and it quickly replaced the older paints. Unfortunately, nobody was yet aware of how poisonous arsenic was, and Scheele —who had a habit of sniffing and tasting his discoveries— succumbed to heavy metal poisoning from exposure to arsenic, mercury, lead, and other chemicals, and he died in 1786. In 1814 a slightly improved version of his recipe became commercially available as Paris Green or Emerald Green. These arsenic-based pigments became popular among artists and manufacturers of cloths, candles, wallpaper, printing ink, and even candies. Of course, in the 1800s, sudden unexplained deaths weren’t unusual, so the Paris Green deaths weren’t immediately recognized. Especially dangerous was its use in wall paint and wallpaper: when moisture degraded the pigment, it released deadly arsine gas. (Napoleon, who died in a bright green room with mildew on the walls, was found to have an unusually high amount of arsenic in his hair and bones.)

True Colors: In the 1890s, Italian authorities became aware of a disturbing trend: more than 1,000 apparently healthy children had died mysteriously in recent years. A chemist investigated their homes and discovered that virtually all of them played in rooms with mildew and Emerald Green wallpaper. Arsine gas, heavier than air, tended to stay close to the floor, where kids sat and played. Countrywide removal of the green wallpaper prevented further deaths.

(Image credit: Flickr user Sarah Barker)

(Image credit: Flickr user Sarah Barker)

Color: Uranium Yellow

Active Ingredient: Uranium oxide ore

How Did That Become a Thing? Unlike equally dangerous radium, which was used in paint on clocks and airplane dials because it glowed, uranium ore’s appeal was its bright yellow-orange color. Used in artworks as far back as ancient Roman times, uranium-based pigment is so bright that it almost seems lit from within. Added to glass water pitchers or kids’ marbles, uranium glows with a ghostly translucent yellow or green, and in pottery glazes, a festive yellow or orange. One popular example: Between 1938 and 1943, and then again from 1959 to 1972, the manufacturer of a popular line of ceramic dinnerwear called Fiesta used a glaze that contained trace amounts of uranium oxide pigments in its “Fiesta Red” orange-red plates and bowls.

True Colors: Slowing sales— not fear of radiation— caused the manufacturer to discontinue the entire Fiesta line by 1973, including Fiesta Red. When the line was reintroduced in 1986, new glazes were used that did not contain uranium oxide. But because uranium oxide has a half-life of 4.5 billion years, if you hold a Geiger counter up to a vintage Fiesta Red plate or bowl, the radiation can still be detected. Because of this, the Environmental Protection Agency cautions collectors of vintage orange-red Fiesta ware against using them to serve food or drink, and to dispose of any cracked or broken pieces.

_______________________________

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader. The 28th volume of the series is chock-full of fascinating stories and facts, and comes in both the Kindle version and paper with a classy cloth cover.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader. The 28th volume of the series is chock-full of fascinating stories and facts, and comes in both the Kindle version and paper with a classy cloth cover.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!