Neatorama is proud to bring you a guest post from history buff and Neatoramanaut WTM, who wishes to remain otherwise anonymous.

At the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, there was found on the Midway an interactive ‘scenograph’ exhibit of something called the “Johnstown Flood”. Similar exhibits concerning this “Johnstown Flood” would later be found at Coney Island in New York and the Atlantic Boardwalk. All were immensely popular with the viewing (and paying) public for reasons that will be made clear.

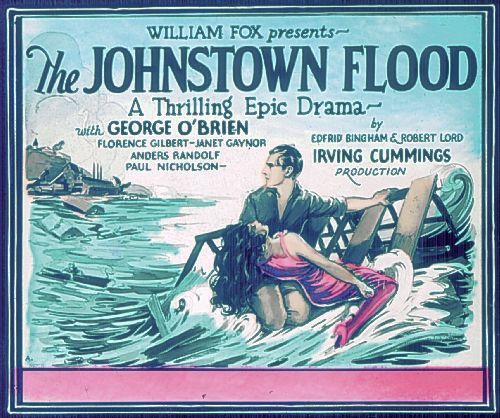

In 1926, there was released a film by the name of The Johnstown Flood, it being the type of drama termed a ‘potboiler’ at the time. From the movie poster below, one can easily deduce that the Johnstown Flood was some sort of epic disaster involving a flood, prominent enough to warrant an exposition midway exhibit and a film.

And in a scene found in the 1931 film Public Enemy, purported to take place in 1909, there is a sign on a wall that states, "Don't Spit ON THE FLOOR Remember the JOHNSTOWN FLOOD!" This sign or facsimile was typically employed in early 20th century restaurants, businesses, and movie theaters, on the silver screen during intermission in theaters and on the walls in other venues, as a gentle reminder in an age when many men chewed tobacco and would spit the results indiscriminately. (A similar reminder of the period was, ‘Do not expect to rate as a gentleman if you expectorate on the floor.’) But what exactly was this ‘Johnstown Flood’ in which there was such interest, especially in films, and why and how did it become such a cultural phenomenon?

Beginning in June 1889, the ‘Johnstown Flood’ entered into American popular culture and stayed there for a couple of generations. The Victorian sentimental approach was used in the first books about the Johnstown Flood, which were full of horrendous eyewitness and survivors’ accounts, all heavy on the pathos. The first book about the flood appeared on June 6, only a week after the disaster, and many more were subsequently rushed into print due to the high demand. These were even sold door-to-door across the United States. There was also poetry composed about the flood (All the horrors that Hell could wish, such was the price that was paid for – fish) and photographs of the flood’s destruction were sold commercially.

In 1889, the flood in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was the biggest news story since the Civil War. Today, the flood is ranked as the third-greatest natural disaster in American history. It was a tragic event involving thousands of fatalities, and, as would also later be the case with the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900, it was an event unprecedented in scope and severity. It involved gross negligence, abuse of power, skullduggery, and callous indifference on the part of wealthy men, a flood of biblical proportion, destruction of entire towns, a heartrending mass death of working stiffs, a horrific climax, and an outrageous miscarriage of justice. It was a perfect storm of occurrences so dramatic that, nearly 130 years later, the Johnstown Flood tragedy remains legend, such that ‘Johnstown Flood’ has become a colloquial term synonymous with ‘disaster’, although many people use the term ‘Johnstown Flood’ without knowing its history or significance.

At the time of the flood, Johnstown was a booming ‘steel town’ that was home to 10,000 people, with 20,000 more living close by in surrounding towns and villages. Founded in 1794, Johnstown was built by the German and Welsh peoples who had settled in the area. An industrial city from its founding, Johnstown continued to prosper with the opening of canal and rail lines. But there was a serious catch.

Pre-flood Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Pre-flood Johnstown, Pennsylvania

There was a problem with Johnstown's location in that it was built on a floodplain at the end of a long sloping valley, at the confluence of the Little Conemaugh and Stonycreek Rivers. Other problems such as increased runoff from the hills due to deforestation as well as the filling in of the riverbanks to create more building space caused flooding to become a regular event in Johnstown. The rivers, which ran down from the Allegheny Mountains to form the town’s eastern, western, and southern borders, frequently overflowed during spring rains, although never severely.  Conemaugh Lake, located in the hills 14 miles north of Johnstown, at the head of the same valley in which Johnstown was at the foot, was a manmade reservoir created in 1853. The state of Pennsylvania had initially built a dam on the South Fork Creek to create a reservoir for the Pennsylvania Canal. Though the dam was initially well-engineered for the day, subsequent alterations and repairs had utilized trees, brush, and even manure, instead of rock and compacted earth, as an economical fill for the dam, which was by then essentially little more than a pile of dirt and rubble dumped across a stream between the two hills that formed the banks of the reservoir.

Conemaugh Lake, located in the hills 14 miles north of Johnstown, at the head of the same valley in which Johnstown was at the foot, was a manmade reservoir created in 1853. The state of Pennsylvania had initially built a dam on the South Fork Creek to create a reservoir for the Pennsylvania Canal. Though the dam was initially well-engineered for the day, subsequent alterations and repairs had utilized trees, brush, and even manure, instead of rock and compacted earth, as an economical fill for the dam, which was by then essentially little more than a pile of dirt and rubble dumped across a stream between the two hills that formed the banks of the reservoir.

Once railroads made the canal obsolete, the reservoir changed hands several times until it was sold in 1879 to a group of fifty wealthy Pittsburgh industrialists and businessmen, who had decided to create a private fishing resort and scenic getaway in the mountains at South Fork, Pennsylvania, this being the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

The club purchased the earthen South Fork Dam, lowered its level so that a carriage road could run along its top, raised the level of the lake, stocked it with fish and built lakeside cottages. However, they did not replace the dam’s underflow discharge pipes, which a previous owner had removed and sold as scrap metal, making it then impossible to relieve a high level in the lake. Although warned in 1881 by a civil engineer that the lake’s dam desperately needed major maintenance and that all previous repair efforts and modifications had actually weakened the dam and made it unsafe, the club ignored the engineer’s recommendations. After all, the club’s owners hadn’t become wealthy men by throwing their money around needlessly.

(Image credit: © Brian W. Schaller/License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

(Image credit: © Brian W. Schaller/License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

After the dam was lowered, it stood only 4 feet above the spillway, and floating lake debris constantly clogged the screens installed to keep the fish from escaping through the spillway. Standing in the hills 450 feet above Johnstown, the dam had already failed once in 1862, but since the Conemaugh Lake reservoir was only half-full at the time, it did little damage in the valley far below. These latest modifications to the dam were of as poor quality as had been the original alterations and all subsequent repairs and did nothing to improve its integrity – or safety.

Many people in the valley towns below wondered why nothing had ever been done to upgrade and strengthen the dam and, realizing their vulnerability, called it "the sword of Damocles". The president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club refused all requests for the dam to be strengthened, saying, "You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise". No qualified civil engineer or hydrologist had ever directed the dam’s numerous repairs, or its subsequent modifications by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Simply put, the South Fork Dam had by then become a ticking time bomb, one that would timeout and detonate during the mid-afternoon of Friday, May 31st, 1889.

The spring of 1889 had been a wet one for the Johnstown area, and Conemaugh Lake was already near full capacity when a megastorm dropped about 10 inches of rain in the 24 hours leading up to May 31st. At 10 AM on May 31, with the lake surface less than a foot from the top of the dam, the club’s president noticed the lake’s level was rising visibly, an ominous circumstance for so large a body of water. When the club’s frenzied attempts to shore up the dam and dig an emergency spillway failed, and with failure of the dam then imminent, he ordered a warning to be wired to Johnstown, a warning that was either never sent or was sent far too late.

(Image credit: Brian W. Schaller)

(Image credit: Brian W. Schaller)

At 3:15 PM, the 72' high and 931' long earthen dam on South Fork Creek, holding back 20 million tons of water (about 5 billion gallons) in the 60-70' deep and two-mile long Conemaugh Lake failed, opening a 270-foot wide breach. The lake emptied out within 45 minutes and the resulting cataract of water cascading down the valley was no less than 30' at times and upward of 90', averaging 40 miles per hour as it destroyed practically everything in its path, including the towns of South Fork, Mineral Point, East Conemaugh, and Woodvale, all located upriver of Johnstown.

View downstream from the failed South Fork Dam

View downstream from the failed South Fork Dam

The immense rush of water scoured the land down to bedrock, uprooted trees, disintegrated brick structures, destroyed railroad tracks, and moved 100-ton locomotives and their rail cars nearly a mile. As it barreled toward East Conemaugh, an eyewitness said the water “just seemed like a mountain coming". It was no Ice Age megaflood, but it was soon to prove disastrous enough.

At 4:07 PM, the flood hit Johnstown with a wave height of almost 40' and within ten minutes, four square miles of a bustling industrial town were turned into wasteland.

The wall of water, now burdened with tons of debris, slammed into Yoder Hill just west of downtown Johnstown and split into three backwash waves. The largest wave crashed into the Stone Bridge railroad overpass, one went back up the valley and one returned to the original path of the flood. The Stone Bridge, upgraded the year before to accommodate increased train traffic, held under the onslaught and the trapped waters, laden with debris, caused Johnstown to be turned into a lake.

A debris field 40' high and 45 acres in size, containing thousands of tons of debris from the valley towns upstream and Johnstown itself piled up against the Stone Bridge as the water drained through. The mass was comprised of buildings, machinery, freight cars, miles of railroad track, bridge sections, telephone poles, lumber, trees, wire, thousands of animals, and hundreds of humans, living and dead.

As was the case in weather disasters such as the Indianola, Texas, hurricane of 1886 and the Tri-State Tornado of 1925, many victims died not directly from the disaster itself but from what followed – fire. When the Gautier Wire Works in Johnstown was destroyed, it unleashed miles of barbed wire it had in inventory, which bound the wreckage and other flood debris tightly together, making escape all but impossible for most of those trapped within. And, as part of the perfect storm, a tank car caught up in the flood spilled thousands of gallons of kerosene amid the piled-up debris.

“The Great Conemaugh Valley Disaster”, lithograph by Kurtz & Allen

“The Great Conemaugh Valley Disaster”, lithograph by Kurtz & Allen

The kerosene-soaked debris field was held against the arches of the Stone Bridge by the current and bound tight by the barbed wire. The few who could escape the pile did so by heading for shore, but many others were still entrapped helplessly in the debris field. Then the ultimate horror occurred: the debris field caught fire, probably from a coal stove or kerosene lantern. The flames spread over the pile as those who had escaped the flood tried to rescue people, some still in the remnants of their homes. The fire was reported to have burned with "all the fury of hell".

Cries for help were slowly but surely superseded by screams of agony as the flames reached those trapped in the debris field. Those onshore could only look on with horror, as there was nothing they could do. With tears in their eyes, the surviving townspeople stopped their ears to shut out the screams, which finally went silent after three days of continuous conflagration.

Eighty people are positively known to have died in the fire, and hundreds more undoubtedly did so. Many of those trapped in the burning debris field, dead and alive, were completely incinerated, leaving no trace.

Recovery of the dead continued for months afterward; it was not until July 10 that a day passed without the recovery of a single corpse. Nearly one in three of the known flood victims were never identified due to decomposition, mutilation, and/or incineration.

Naturally, there were lawsuits brought against the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, but many of the club’s members were ‘robber barons’, men who had parlayed their fortunes and influence into great political power and pull. One such member was Andrew Carnegie, a man worth an estimated $500 million at a time when a typical workingman in Johnstown made about $1000 a year. Even in the late 19th century, there were those who were “too big to jail”.

When word of the dam's failure was telegraphed to Pittsburgh, the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club gathered to form the Pittsburgh Relief Committee for providing assistance to the flood victims as well as agreeing never to speak publicly about the club, the dam, or the flood. This strategy was a success. Although the Johnstown Flood betrayed the hand of man in its creation, judges ruled it an Act of God. All lawsuits brought against the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club failed, and not a cent in damages was ever paid to anyone.

Ordinary Americans were outraged that a slipshod dam, carelessly and incompetently modified at the behest of wealthy men for their pleasure, had contributed to the deaths of over two thousand people like themselves. Though the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club had escaped any legal liability for the disaster, they did realize that the local populace was understandably inflamed over the event, and the club was broken up before an angry mob came calling with torches and pitchforks. Ironically, the old South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club clubhouse today houses a museum of the Johnstown Flood.

(Image credit: Niagara)

(Image credit: Niagara)

As is often the case, some good did result from all the bad. The perceived injustice of the exonerating verdicts and the resulting public outrage did cause tort reform to be effected and helped inspire the acceptance of “strict, joint, and several liability”, which supports the idea that a “non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land.” Were the 1889 Johnstown Flood to occur today, millions, if not billions, in damages would be owed the victims.

Location where the Conemaugh Lake dam failed, causing the Johnstown Flood. (Image credit: JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD)

Location where the Conemaugh Lake dam failed, causing the Johnstown Flood. (Image credit: JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD)

Many of the flood's known victims are buried in Johnstown’s Grandview Cemetery. A section of the cemetery called the "Unknown Plot" contains the bodies of 777 flood victims who could not be identified. Three years after the flood, on May 31, 1892, a "Monument to the Unidentified Dead" was unveiled at the cemetery. Made of granite and standing 21 feet tall, the monument is topped by three allegorical women: Faith, Hope, and Charity. Hope points heavenward, indicating the presumed final destination of the Unidentified Dead.

(Image credit: Ron Shawley)

(Image credit: Ron Shawley)

It took five years to rebuild Johnstown, which again endured deadly floods in 1936 and 1977. Johnstown has come to be known as “Flood City”, to the dismay of the Johnstown Chamber of Commerce. And, with Johnstown’s unfortunate topography, it is certain that additional floods will continue to occur. History may not repeat itself, but it will most certainly rhyme again someday.

Facts About the Johnstown Flood

* At least 2,209 people are known to have lost their lives. Just as would also be the case for the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900, the exact number of flood victims will never be known

* It is estimated that at least 900 flood victims were never found, their remains either being lost in the river downstream of Johnstown or incinerated at the Stone Bridge

* 99 entire families were killed

* 124 women were left widows

* 198 men were left widowers

* 396 children aged ten or less were killed

* 98 children lost both of their parents

* Bodies of flood victims were found as far away as 600 miles, in Cincinnati

* Remains of flood victims were still being found as late as 1911 and there is no reason to believe that all such remains have been found

* 1,600 homes were destroyed

* 280 businesses were destroyed

* $17 million in property damage was done to Johnstown alone

Sources and Further Reading

Black Friday

Mass Grave of Johnstown's Unknown Dead

National Geographic

The Disaster Which Eclipsed History: The Johnstown Flood by R. K. Fox

Pennsylvania Highways

Tracing history of Johnstown, Pa.'s flood of 1889

How the Johnstown flood has been memorialized through the years

Great Disasters of the 19th Century

Pan-American Exposition

Johnstown Flood Victims Gravesite

Johnstown Flood Victims

YouTube: The Johnstown Flood of 1889

YouTube: Simulation of the Dam Break and Flood

YouTube: South Fork Dam Than and Now

Her body was buried with the unknown dead, but five months later was identified by her father.

The search was apparently successful. Sorry for your family's loss.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/109826950/grace-ida-garman