Neatorama is proud to bring you a guest post from history buff and Neatoramanaut WTM, who wishes to remain otherwise anonymous.

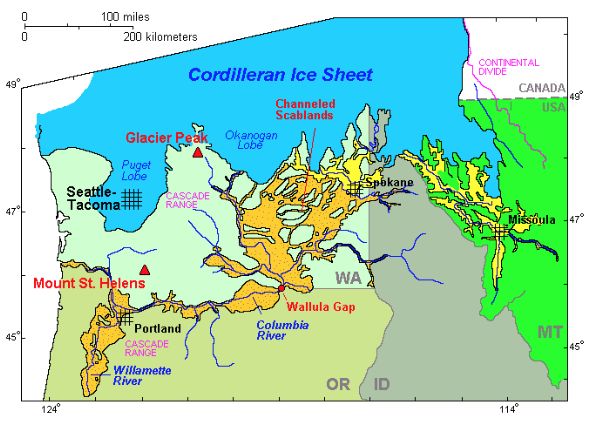

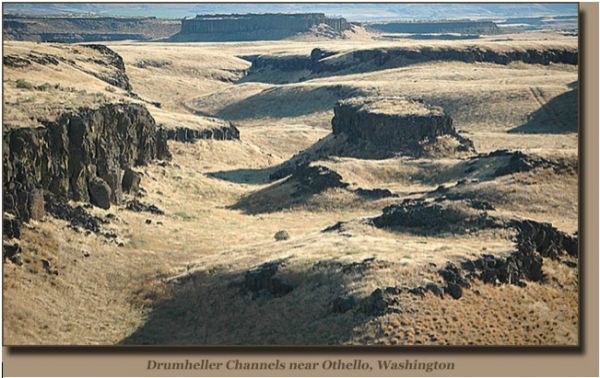

When the Lewis and Clark Expedition made its way through the Pacific Northwest circa 1805, the expedition’s team saw an alien landscape the likes of which no one had ever seen before. Vast stretches of land that had no topsoil whatsoever. A dry waterfall that was miles across. Enormous holes carved out of hard volcanic basalt bedrock. Huge boulders in the middle of an otherwise desolate flat prairie. Gravel bars that resembled those seen elsewhere in small creeks, but that were miles long and hundreds of feet high. These and other similar anomalies presented one of the world’s premier geologic mysteries, a mystery that would confound geologists and other scientists for more than a hundred years.

The Dry Falls, 3.5 miles wide. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

The Dry Falls, 3.5 miles wide. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Today we know the cause of these geological enigmas –megafloods- the like of which the earth had not known since its creation. The flow of a megaflood was more than ten times the combined flow of all the rivers on earth, and these megafloods occurred perhaps as many as a hundred times before ceasing due to climate change.

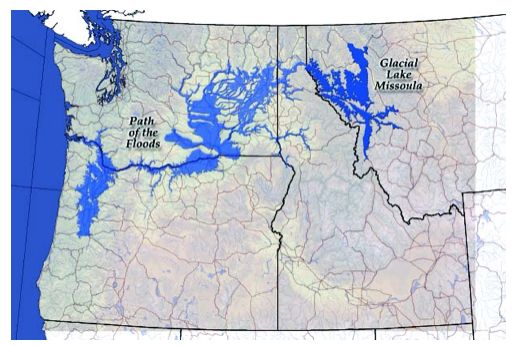

All evidence indicates that these megafloods, known today as the Lake Missoula Floods, occurred between 11,000 and 19,000 years ago. The largest such flood, identified by the depth of its sediments, is estimated to have occurred about 15,000 years ago, tearing across far western Montana, far northern Idaho, eastern Washington, and northern Oregon en route to the Pacific Ocean.

It was these inconceivably enormous megafloods that scoured topsoil away down to the hard basalt bedrock and then blasted huge holes as deep as a hundred feet in that bedrock. It was these same megafloods that carried hundred-ton boulders on ice rafts across four states, created the largest waterfall the world has ever known, and carved the topography of much of eastern Washington State into what are today known as the Channeled Scablands. A prominent geologist, the hero of this story, was later to write, "The popular name ‘Scablands’ is an expressive metaphor. The Scablands are wounds only partially healed in the epidermis of soil."

Channeled Scablands. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Channeled Scablands. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Just how large were these megafloods? Imagine a miles-long glacial ice dam a half-mile high, holding back an immense freshwater lake 2000 feet deep, containing an estimated 500-600 cubic miles of water, maybe as much as 700 trillion gallons altogether. Then imagine the flood resulting from a mile-wide section of that ice dam failing catastrophically, with the glacial lake then emptying itself within 48 hours after tearing away the remainder of the ice dam. That’s an average flow of about 4.5 billion gallons per second (the maximum flow of the Amazon River is about 100 million gallons per second), and the initial flow upon bursting of the ice dam may have been 10 times as great. And it happened again and again, with an estimated 50-100 years between ‘refills’ of the glacial lake, as after each megaflood, the broken lobe of the glacier crept down the valley again, building another dam.

These megafloods all flowed west and southwest toward the Pacific Ocean, and the amount of water involved was so immense that it is estimated to have covered what is today Portland, Oregon over four feet deep by the time it reached that location. All of the numerous Lake Missoula Flood streams, having once spread out over a vast area, converged at Washington State’s Wallula Gap, a mile wide chasm more than 800 ft deep. Even this huge opening was insufficient to pass the megaflood’s colossal discharge, and it created a virtual dam that accumulated the stalled floodwaters into a vast temporary lake known today as Lake Lewis. These waters also carried millions of tons of sediment, much of which settled out while the waters awaited passage through the gap. Today, the sediment deposited from these megafloods can be observed, like a giant layer cake, and have given geologists an opportunity to identify how many of these individual megafloods there were and their severity.

Wallula Gap. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Wallula Gap. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

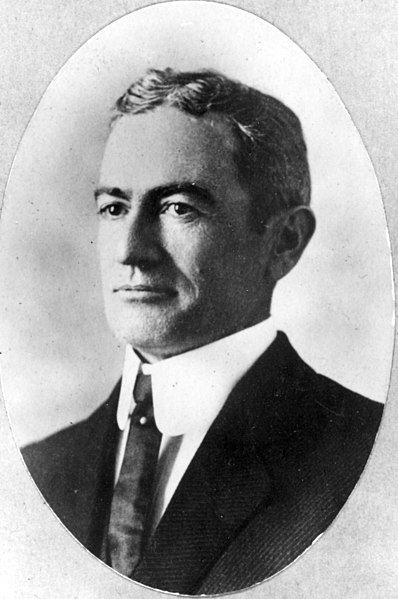

Viewing today’s satellite imagery and aerial photography, it is obvious that water, and a lot of it, had been instrumental in forming the Scablands. But back in the early 1920’s such a thing was not possible and it is only by dint of lengthy, intense, and careful field study that a United States Geological Survey (USGS) geologist named J Harlen Bretz was at last able to crack the mystery, concluding that water in the form of a megaflood must have been responsible for forming the Scablands.  J. Harlen Bretz was born on September 2, 1882, in Saranac, Michigan. Becoming interested in the sciences at an early age, Bretz in 1913 obtained a PhD in Geology and, after brief teaching stints, went to work for the USGS. Bretz’s first exposure to the Scablands resonated deep within, for he became obsessed with finding the explanation behind their mysterious formation. He spent as much time as possible in their study, subjecting his long-suffering family to an annual ‘vacation’ of camping in the Scablands for weeks at a time under the most primitive of conditions. At last, having satisfied himself as to the details concerning the origin of the Scablands, he wrote several papers on the subject from 1923-1927 and submitted them for peer review. His 1927 paper was presented to a group of geologists in Washington, D.C., and Bretz’s theory about the magnitude of his hypothetical megaflood was rejected as wholly inadequate, incompetent, and outright preposterous.

J. Harlen Bretz was born on September 2, 1882, in Saranac, Michigan. Becoming interested in the sciences at an early age, Bretz in 1913 obtained a PhD in Geology and, after brief teaching stints, went to work for the USGS. Bretz’s first exposure to the Scablands resonated deep within, for he became obsessed with finding the explanation behind their mysterious formation. He spent as much time as possible in their study, subjecting his long-suffering family to an annual ‘vacation’ of camping in the Scablands for weeks at a time under the most primitive of conditions. At last, having satisfied himself as to the details concerning the origin of the Scablands, he wrote several papers on the subject from 1923-1927 and submitted them for peer review. His 1927 paper was presented to a group of geologists in Washington, D.C., and Bretz’s theory about the magnitude of his hypothetical megaflood was rejected as wholly inadequate, incompetent, and outright preposterous.

It had all begun with Bretz’s study of a USGS topographic map of the Scablands. Identified on the USGS map were several huge cliffs and potholes. Undoubtedly, they had once been waterfalls, but they were now dry. These huge potholes gave Bretz the first clues that a catastrophic event of biblical proportions had occurred. He wrote, "I could conceive of no geological process of erosion to make this topography except huge, violent rivers of glacial meltwater."

Potholes drilled into basalt. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Potholes drilled into basalt. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Bretz’s theory did have a then-fatal shortcoming; he could not satisfactorily explain where the water required for such a megaflood could have come from. Although he gamely tried, theorizing that erupting volcanoes under the glacial ice sheet could have been responsible, his peers quickly calculated that such a thing was impossible and they laughed him to scorn. Bretz became a laughingstock and an object of ridicule in the field of Geology and would remain that way for well over a decade.

But for all that, Bretz had one great advantage over his peer critics. Although they were all highly educated men and experienced professional geologists, none of these others had ever been to the field to investigate the Scablands, whereas Bretz had logged many hundreds of hours doing just that. Thus these ‘armchair detectives’ were passing judgment on phenomena that they had never personally examined, or even seen, and they would all live to rue the day.  Bretz became an outcast, having gone into a sort of self-imposed exile, stating that he had already said all there was to say on the subject. And then, on June 18, 1940, at a convention of earth scientists, a USGS geologist named Joseph Thomas Pardee gave a short presentation about ripple marks in a prehistoric lakebed. Years before, Pardee had written a paper describing an ancient glacial lake, Lake Missoula, that evidence suggested had filled numerous valleys in western Montana during the Ice Age. It had been created when the lobe of an advancing glacier dammed the Clark Fork River. From the high water marks in the mountains above Missoula, Montana, Pardee estimated that the lake had been some 500-600 cubic miles in volume. Most geologists knew about Lake Missoula, but there had been no compelling evidence that the Lake Missoula ice dam had ever failed. Pardee now offered exactly that.

Bretz became an outcast, having gone into a sort of self-imposed exile, stating that he had already said all there was to say on the subject. And then, on June 18, 1940, at a convention of earth scientists, a USGS geologist named Joseph Thomas Pardee gave a short presentation about ripple marks in a prehistoric lakebed. Years before, Pardee had written a paper describing an ancient glacial lake, Lake Missoula, that evidence suggested had filled numerous valleys in western Montana during the Ice Age. It had been created when the lobe of an advancing glacier dammed the Clark Fork River. From the high water marks in the mountains above Missoula, Montana, Pardee estimated that the lake had been some 500-600 cubic miles in volume. Most geologists knew about Lake Missoula, but there had been no compelling evidence that the Lake Missoula ice dam had ever failed. Pardee now offered exactly that.

The ripple marks Pardee described were up to 50 feet high and had a wavelength as great as 500 feet. These ripple marks could only have been made by a vast flow of water, which could have happened only if the ice dam that had created the glacial lake suddenly failed. As Pardee proposed it, river water cut a channel through the base of the ice dam, creating a weak point that continued to enlarge. Hydrostatic pressure from the deep lake waters eventually caused the weakened dam to stress-fracture catastrophically at that point, after which Lake Missoula rocketed through an opening in the glacial dam that was at least a mile wide. And where would those many trillions of gallons of water have gone? Directly into the Channeled Scablands.

Glacial Lake Missoula Ice Dam. Image courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Glacial Lake Missoula Ice Dam. Image courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

All of the conference participants sat in stunned silence, for, to a man, they realized that this proposed Glacial Lake Missoula Flood was Bretz’s hypothetical megaflood.

Bretz was vindicated. Only his most vocal critics remained adamant, but when James Gilluly, among the most antagonistic of them, finally visited the the Scablands, he stood for a long time looking glumly at the gigantic escarpment and plunge pool of a once-enormous waterfall before muttering, “How could I have been so wrong?”

How, indeed? His peers didn’t let him forget it, either. An anonymous bard of the USGS's Pick and Hammer Club wrote, circa 1952:

A glacier once ‘neath its collar got hot

And out o’er the scablands a mighty flood shot.

Now truly, Gilluly, t’ will fool ye,

For Bretz has been there and he says there is not

A shadow of doubt what occurred on that spot.

‘Tis true, it has Jim Gilluly’s goat got.

But speaks he not truly, Gilluly?

In 1979, at age 96, Bretz received the Penrose Medal, the highest honor for a geologist. When asked by his son how it felt to be vindicated and recognized after so many years of professional scorn and abuse, Bretz replied, perhaps jokingly, "All my enemies are dead, so I have no one to gloat over".

Giant Current Ripples. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Giant Current Ripples. Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

J. Harlen Bretz died on February 3, 1981. His legacy is sound, and the work he pioneered continues to this day. Concerning the mystery of the Channeled Scablands that he alone had solved in the face of ferocious opposition, he left us with the following words:

Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Photograph courtesy of Tom Foster at hugefloods.com

Though he was the consummate scientist, Bretz once let his enthusiasm and admiration for the Channeled Scablands show through the austere language of a scientist. He was not just academically and professionally intrigued; he was in personal awe of the Scablands. Concerning their unique status among all of the world’s natural wonders, he wrote, "Let the observer take the wings of the morning to the uttermost parts of the earth; he will nowhere find its likeness."

Sources and Further Reading

Huge Floods

National Geographic

The Seven Wonders of Washington State

University of Wisconsin

Glacial Lake Missoula

State of Washington Department of Mines and Geology

J Harlen Bretz And The Great Scabland Debate

Bretz, J Harlen (1882-1981), Geologist

The Channeled Scablands of the Columbia Plateau

The Journal of Geology

Glacial Lake Missoula

Mountains on the Move

The Floods That Carved the West

J. Harlen Bretz at Find a Grave

J.T. Pardee at Find a Grave

Glaciers of Montana

The Missoula Flood

Explore the Scablands

Channeled scablands of eastern Washington: the geologic story of the Spokane flood

Trike Flying at Palouse Falls

James Gilluly

James Gilluly 1896—1980

(Image credit: Steven Pavlov)