The following article is from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader.

(Image credit: Sgt Ian Forsyth RLC/MOD)

(Image credit: Sgt Ian Forsyth RLC/MOD)

Throughout most of history, if you lost a limb, the replacement of choice was a wooden peg (which only looked cool if you were a pirate). But that all changed after a young soldier lost a leg in the Civil War and refused to take his injury lying down.

WALKING TALL

“You’ll dance again, but it’s going to take a year.” That’s the kind of thing that Dr. Mac Hanger III tells a lot of his patients. As one of the world’s leading prosthetists, it’s his job to fit amputees with new limbs and help them acclimate to them. For example: Hanger helped several maimed victims of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings get their lives back. Losing a limb once meant losing your quality of life, but that’s not so anymore. “People really become different people,” Hanger says. “You lose a leg, but you gain a lot of wisdom and strength.” He should know, because that’s exactly what happened to his great-great-grandfather, J. E. Hanger. And that’s how the modern prosthetics industry was born.

CASUALTY OF WAR  On June 3, 1861, the first land battle of the Civil War took place in Philippi, Virginia. Early that morning, an 18-year-old Confederate soldier named James Edward Hanger was standing guard outside a stable where his fellow soldiers were sleeping. Private Hanger had enlisted only two days earlier. He’d dropped out of engineering school to join his brothers in the Confederate Army. But his career as a soldier would be short-lived. Just after dawn, Hanger heard gunfire, so he ran inside the stable to get his horse. Just then a six-pound cannonball tore through the barn and struck his left leg.

On June 3, 1861, the first land battle of the Civil War took place in Philippi, Virginia. Early that morning, an 18-year-old Confederate soldier named James Edward Hanger was standing guard outside a stable where his fellow soldiers were sleeping. Private Hanger had enlisted only two days earlier. He’d dropped out of engineering school to join his brothers in the Confederate Army. But his career as a soldier would be short-lived. Just after dawn, Hanger heard gunfire, so he ran inside the stable to get his horse. Just then a six-pound cannonball tore through the barn and struck his left leg.

With only a bit of skin keeping his lower leg attached, Hanger crawled to a corner of the barn to hide… and passed out. The next thing he knew, Union soldiers had him on a table, and he was writhing in pain. Unable to save the leg, two field surgeons spent an hour with a jagged saw cutting through Hanger’s skin, muscle, and bone a few inches above his knee. The surgeon then cauterized the wound with a hot iron. The excruciating amputation saved Hanger’s life. But what kind of life would that be?

Private Hanger spent the next two months as a prisoner of war in a Union hospital. “I cannot look back upon those days in the hospital without a shudder,” he later said. “In the twinkling of an eye, life’s fondest hopes seemed dead. I was the prey of despair. What could the world hold for a maimed, crippled man?” In those days most amputees, unable to work, ended up begging on the streets.

After a prisoner exchange, the teenager was relieved of duty. He arrived home in Churchill, Virginia, fitted with a heavy wooden pegleg that was painful to wear and difficult to get around in. He hobbled upstairs to his room and asked his parents to leave him alone. But Hanger didn’t spend his time wallowing in self-pity. The former engineering student studied his wooden “Yankee leg” and quickly realized that its main problem was that it had little in common with a real leg. So Hanger decided to make one himself.

WHEN LIFE GIVES YOU LEMONS…

Three months after retreating to his room, Hanger walked down the stairs without the aid of crutches. His family was astonished. Gone was the pegleg; in its place was the world’s first articulated prosthetic limb. Hanger made his contraption out of oak barrel staves—staves— the narrow strips of wood that form the sides of a barrel— which were more flexible than a solid piece of hardwood. Then he’d added hinged joints at the ankle and the knee. This not only made walking easier, but also sitting down and getting up. Hanger even carved himself a wooden foot so he could wear two shoes again. Best of all: the artificial limb weighed only about five pounds. All of a sudden, a new world opened up for Hanger. And it was about to open up for a lot of other wounded veterans as well.

Three months after retreating to his room, Hanger walked down the stairs without the aid of crutches. His family was astonished. Gone was the pegleg; in its place was the world’s first articulated prosthetic limb. Hanger made his contraption out of oak barrel staves—staves— the narrow strips of wood that form the sides of a barrel— which were more flexible than a solid piece of hardwood. Then he’d added hinged joints at the ankle and the knee. This not only made walking easier, but also sitting down and getting up. Hanger even carved himself a wooden foot so he could wear two shoes again. Best of all: the artificial limb weighed only about five pounds. All of a sudden, a new world opened up for Hanger. And it was about to open up for a lot of other wounded veterans as well.

Hanger had the dubious distinction of being the Civil War’s first amputee, but he was far from the last. By the time the conflict ended four years later, at least 60,000 other soldiers had suffered similar fates. Now that Hanger was back on his “feet,” the 18-year-old decided to open his own prosthetics business, and two years later he patented his first “Hanger Leg.” Rival inventors were attempting to create artificial limbs as well, but thanks to Hanger’s superior design, in 1864 the Association for the Relief of Maimed Soldiers chose his company to supply prosthetics for wounded men. He was awarded a grant of $20,000 and got to work. By the time the war ended, thousands of amputee soldiers were sporting Hanger prosthetics.

STAND AND DELIVER

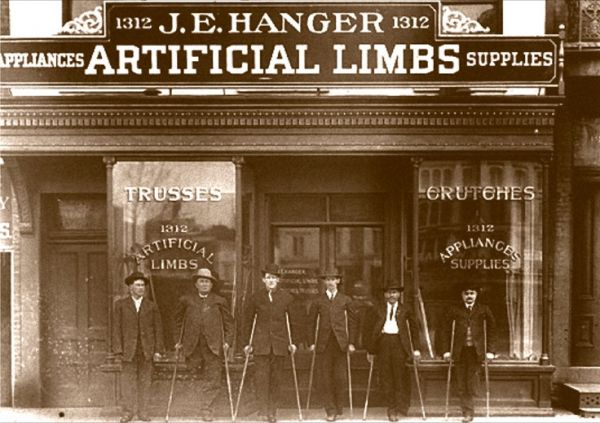

Hanger was just getting started: he married in 1873 and would father eight children. By 1888 his company had grown so large that he moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C., and then expanded into other cities. Hanger died in 1919. Today, Hanger Orthopedic Group, Inc. is a billion-dollar corporation that employs nearly 5,000 people and fits about a million people with new limbs every year.

LASTING LEG-ACY

A lot has changed since Hanger’s first articulated leg, but the goal of prosthesis design remains the same: to mimic natural movement as much as possible. The biggest difference with today’s limbs is what they’re made of. In fact, modern prosthetics look like something out of a superhero movie. Patients are fitted with space-age materials that are lighter and stronger than ever before. Robotic knees can anticipate where the wearer wants to go and help them go there. The next step in prosthetics, already underway, is hooking up people’s artificial hands to their brains so they can open and close their fingers just by thinking about it. And stroke victims who have lost the use of their limbs are fitted with prosthetic exoskeletons that respond to their brain activity. This technology isn’t cheap— a new limb will run you from $ 6,000 to upward of $ 70,000 for the really fancy ones. (Hopefully, as the technology improves, getting a new limb won’t cost an arm and a leg.)

Mac Hanger III is proud that, thanks to modern technology, an amputee can come to his office with just a stump and leave with a new limb that same day. “As they get up on a prosthesis,” he says, “particularly these new ones with more responsive technology, you can see hope return to their eyes.”

_______________________________

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader. The 28th volume of the series is chock-full of fascinating stories and facts, and comes in both the Kindle version and paper with a classy cloth cover.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Factastic Bathroom Reader. The 28th volume of the series is chock-full of fascinating stories and facts, and comes in both the Kindle version and paper with a classy cloth cover.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!