The following is an article from the book Uncle John’s Perpetually Pleasing Bathroom Reader.

The following is an article from the book Uncle John’s Perpetually Pleasing Bathroom Reader.

There’s a lot being said about climate change these days. Most people (and most scientists) think it’s happening now; some say it’s a myth. Wherever you stand on the issue, we can’t help but wonder what you would have thought if you’d been around in 1815.

(Image credit: Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons)

It all started with a volcano. On April 5, 1815, Mount Tambora blew its top. The massive eruption lasted ten days and completely ravaged the Indonesian island of Sumbawa. Residents who managed to survive the mountain’s initial fury— and the ensuing tsunami— became victims of deadly lung infections caused by all the ash and toxic fumes in the air. The eruption, which was one of the most powerful in recorded history, ejected more than 10 cubic miles of volcanic material. The islands were blanketed with it, causing crops across Indonesia to fail, and creating a massive food shortage for Asia throughout the spring and summer months.

But that was just the beginning. Mount Tambora’s outburst was only one of many in a string of uncharacteristically high volcanic activity around the globe. The ash from Tambora combined with the enormous amounts of dust and debris already floating in the atmosphere from eruptions in the Philippines, Japan, and the Caribbean. This meant bad news for farmers.

(Image credit: Giorgiogp2)

(Image credit: Giorgiogp2)

EASTERN FRONT

When there’s that much dust, gas, and debris in the air, it gets in the way of sunlight. All that volcanic material started affecting the weather and quickly impacted temperatures around the world. The first areas to get hit were in Asia. Cooler than usual weather caused thousands of Chinese farmers to lose their livestock, particularly water buffalo— beasts of burden on which they depended for harvesting crops. Not that there was much of a crop to harvest: The frigid temperatures ravaged rice fields; even trees started dying off. Heavy monsoons in India led to a massive outbreak of cholera, a water-borne disease, that reached as far away as Moscow.

WESTERN FRONT

As the ash drifted into the Northern Hemisphere, the eastern seaboard of the United States experienced a very cold spring. Even stranger, New England was beset with a “dry fog” that would not dissipate. The lingering fog dimmed and refracted the sunlight, creating a constant eerie red glow in the sky. Even heavy rainfall failed to disperse it.

In eastern Canada and the northern U.S., temperatures routinely fell below freezing through May of 1816— far past the usual Canadian cold season. That, of course, caused crops to fail up and down the east coast of North America. And it just stayed cold. Snow fell on June 4 throughout the region. A storm in Quebec City on that day dropped over a foot of snow. As spring moved into “summer,” lakes and rivers as far south as Pennsylvania iced over. Temperatures fluctuated wildly in some areas, hitting 95°F, then rapidly dropping to below freezing after sunset.

The bizarre weather ravaged food supplies. In the autumn, when many crops are harvested, cornfields across New England were destroyed by early frost. The cost of grains skyrocketed. Limited supplies caused the price of oats alone to jump by 750 percent in many areas. And while some American farmers were able to harvest their fields despite the weather, transporting produce to market on icy roads was all but impossible.

Even Thomas Jefferson was impacted. Already deeply in debt, the former president saw his money troubles worsen as bad weather destroyed the crops at his Virginia plantation, Monticello. The following winter, temperatures dropped into the negative 20s in New York City, freezing the Upper Bay. The ice was so thick that the locals could— and did— ride sleighs from Brooklyn over the river to Governors Island.

BLOODY SNOW

The situation in Europe was even worse, where the weather exasperated conditions in a region trying to rebuild after the devestation caused by the Napoleonic Wars. Wales was hit so hard that refugees fled to England’s major cities, begging for food and shelter. Already limited food supplies ran low, and prices skyrocketed in Germany and Ireland.

Abnormal rainfall caused rivers to rise, while many areas endured frost in mid-August. Elsewhere, people in temperate countries such as Hungary and Italy reported snowfall throughout the summer months. And the dust in the atmosphere turned the white snowflakes red.

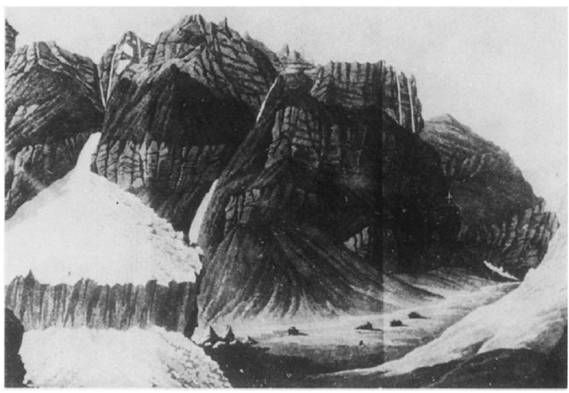

Switzerland was hit particularly hard. Temperatures there were so low that an ice dam formed beneath the Giétro Glacier in the Swiss Alps, creating an artificial lake in the process. The dam eventually burst in the summer of 1818, sending millions of gallons of water into the valley below. Towns were destroyed and thousands of people were killed in what has become known as one of Switzerland’s worst natural disasters.

As thousands starved— and thousands more would— demonstrations began to take place outside of grain markets and bakeries across Europe… and they quickly turned into riots, followed by arson and looting. Still, there wasn’t much that governments could do: The famine was the worst the continent would experience in the 19th century. By the time it was all over, nearly 200,000 Europeans would perish.

LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

But it wasn’t all bad. A shortage of oats to feed horses helped encourage German inventor Karl Drais to create an alternative form of transportation. He called it the Laufmaschine (“ running machine”), and it was a precursor to the modern bicycle. All the material in the air led to somepretty spectacular sunsets that summer, too. British artist J.M.W. Turner created several now-famous paintings that celebrated the unusually yellow atmospheric conditions. And when 19-year-old novelist Mary Shelley found herself stuck indoors during an unseasonably rainy vacation at Lake Geneva that July, she and her colleagues passed the time by trying to frighten each other with scary stories. She came up with one about a scientist who uses various body parts stolen from a cemetery to bring a man back to life— Frankenstein. Her friend, English poet Lord Byron, came up with an idea for a book about a bloodsucking ghoul. He never finished it, but gave it to his friend John William Polidori, who wrote a novella called The Vampyre, which in turn inspired Bram Stoker to write Dracula.

While the foul weather was inadvertently creating the horror genre in Europe, it sent thousands of farmers fleeing from New England. In Vermont alone, over 10,000 people left the state for warmer climates. Many of them flooded into the Midwest and helped tame the wild American heartland. Among those who left Vermont was the family of a young man named Joseph Smith. The Smiths eventually settled in Palmyra, New York. It was a move that led to a series of events that culminated in Smith’s publishing the Book of Mormon and founding the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints years later.

POINTING THE FINGER

Back then, nobody really knew what had caused the devastation and mayhem. Half-baked theories ran rampant. Many Christians pointed at “sinners,” and a few evangelists claimed that the cold was the beginning of the apocalypse. Others believed that the weird weather was somehow the delayed result of Benjamin Franklin’s experiments with electricity. Some even suspected that the Freemasons had something to do with it. Astronomers noted unusual sunspot activity and theorized that the frosty temperatures must have been caused by them.

(Image credit: Jialiang Gao/peace-on-earth.org)

(Image credit: Jialiang Gao/peace-on-earth.org)

Today, climatologists know that Tambora was the cause. Scientists excavating in Iceland have uncovered unusually large deposits of sulfur in the soil layers that date to the early 1800s. Their explanation: the sulfuric acid that comprised the major portion of the gases spewed by the volcano hung in the air and drifted around the world. The gasses acted like mirrors and reflected the sunlight back into space, preventing it from reaching Earth. Whatever people may have thought was the cause, a Vermont woman named Eileen Marguet captured the misery of that dark summer in this poem:

It didn’t matter whether your farm was large or small.

It didn’t matter if you had a farm at all.

’Cause everyone was affected when water didn’t run.

The snow and frost continued without the warming sun.

One day in June it got real hot and leaves began to show.

But after that it snowed again and wind and cold did blow.

The cows and horses had no grass; no grain to feed the chicks.

No hay to put aside that time, just dry and shriveled sticks.

The sheep were cold and hungry and many starved to death,

Still waiting for the warming sun to save their labored breath.

The kids were disappointed, no swimming, such a shame.

It was in 1816 that summer never came._______________________________

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Perpetually Pleasing Bathroom Reader. The 26th annual edition of Uncle John’s wildly successful series is all-new and jam-packed with the BRI’s patented mix of fun and information.

The article above is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Perpetually Pleasing Bathroom Reader. The 26th annual edition of Uncle John’s wildly successful series is all-new and jam-packed with the BRI’s patented mix of fun and information.

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts. If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

http://youtu.be/xEXMJMEARcc