was teeming with tourists. Over the course of the season, 10 million people from 35 countries poured into Fairmount Park to take in the sights at the first-ever World’s Fair in America. Visitors marveled at working elevators, electric lights, and a live walrus. American Indians stood on display, living cultural exhibits for fairgoers to gawk at. The programming changed daily; prizefights, races, and parades were all used to lure day-trippers. On Delaware-Maryland-Virginia Day, there was even a jousting match. But one spectacle drew extra attention- a gigantic disembodied arm that towered four stories above the fairground.

was teeming with tourists. Over the course of the season, 10 million people from 35 countries poured into Fairmount Park to take in the sights at the first-ever World’s Fair in America. Visitors marveled at working elevators, electric lights, and a live walrus. American Indians stood on display, living cultural exhibits for fairgoers to gawk at. The programming changed daily; prizefights, races, and parades were all used to lure day-trippers. On Delaware-Maryland-Virginia Day, there was even a jousting match. But one spectacle drew extra attention- a gigantic disembodied arm that towered four stories above the fairground.

A late entrant to the festival, the lonely, torch-bearing limb wasn’t included in the official guide. Few knew that it was destined to become part of an even bigger statue, meant to be a gift from France to America. Instead, fairgoers simply saw the sculpture as the best way to catch a glimpse of the surrounding counties. They flocked to climb up the arm and stand on the torch’s balcony, forking over 50 cents apiece for the experience. In the space where the statue’s giant elbow should have been, a sculptor stood anxiously, hustling photos and scrap metal from his makeshift souvenir stand. If he had any chance of completing his masterpiece, he’d need all the extra cash he could get.

How War Led to Lady Liberty

The story of the statue begins with the American Civil War. When fighting broke out in 1861, the rest of the world watched with rapt attention: Could the grand experiment in democracy survive? The United States had been an inspiration to the French, who were locked in a cycle of extremism, swinging between bloody democratic revolutions and imperial autocracy. When Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865, the French were crushed. More than 40,000 grieving citizens contributed to a fund to award Lincoln’s widow a gold medal.

It was in this climate, in the summer of 1865, that a group of prominent Frenchmen were discussing politics at a dinner party given by Edouard René de Laboulaye, a prominent historian and law professor. France was still under the thumb of Napoleon III, but when Laboulaye looked to America, he was inspired by "a people intoxicated with hope." He proposed that France give America a monument to liberty and independence in honor of her upcoming centennial. After all, tens of thousands of Frenchmen had just contributed to a medal for Mary Todd Lincoln-how much harder could it be to pony up for a statue?

Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, an up-and-coming sculptor, was excited by the idea. As his mind raced, he pictured the colossi of Egypt, the twin 60-foot, 720-ton sandstone statues of seated pharaohs. Bartholdi wanted his monument to be just as inspiring, and his sketches leaned on the popular imagery of the time-broken chains, upheld torches, crowns meant to represent the rising sun. But Bartholdi also wanted to break from French tradition. Instead of depicting liberty as a half-naked barricade stormer, the artist’s Neoclassical goddess would look staid and calm. Bartholdi didn’t want "Liberty Enlightening the World" to be just a tribute to American freedom. The statue had to send a pointed message to France that democracy works. It didn’t take long for Bartholdi to perfect his vision for the sculpture. Getting the statue actually built, however, was another matter.

Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, an up-and-coming sculptor, was excited by the idea. As his mind raced, he pictured the colossi of Egypt, the twin 60-foot, 720-ton sandstone statues of seated pharaohs. Bartholdi wanted his monument to be just as inspiring, and his sketches leaned on the popular imagery of the time-broken chains, upheld torches, crowns meant to represent the rising sun. But Bartholdi also wanted to break from French tradition. Instead of depicting liberty as a half-naked barricade stormer, the artist’s Neoclassical goddess would look staid and calm. Bartholdi didn’t want "Liberty Enlightening the World" to be just a tribute to American freedom. The statue had to send a pointed message to France that democracy works. It didn’t take long for Bartholdi to perfect his vision for the sculpture. Getting the statue actually built, however, was another matter.

Crowdfunding a Statue

Given the statue's message, backing from the French government seemed unlikely. That meant all the funds—originally estimated at 400,000 francs (more than $2 million today)—had to come from the French people. Laboulaye had an idea: What if he and Bartholdi pitched the project as a joint venture between the two countries? As a show of their shared friendship, France could provide the statue and America the pedestal.

Bartholdi was tasked with convincing Americans to join in. In June 1871, he packed up a small clay model of the statue and set sail across the Atlantic. The sculptor, who spoke almost no English, knew he’d been charged with a difficult job but didn’t realize just how difficult it would be. Most Americans he contacted couldn’t grasp why their country would want a giant torch-wielding monument, much less why they’d help pay for it. After an exhausting four-month tour, Bartholdi returned to France, no closer to financing the pedestal.

Thankfully, fundraising there was proceeding at a better pace, thanks to a national lottery and image-licensing deals. Companies lined up to plaster Lady Liberty’s image on everything from "nerve tonics" to cigars, and they were willing to pay for it. As funds trickled in, Bartholdi began work on the torch and arm. In 1876, he sent the pieces to the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, hoping that it would motivate Americans to open their wallets. Finally, his efforts were beginning to pay off.

That same year, a group called the American Committee assembled to boost the fundraising-and an inter-city competition heated up. Bartholdi and his supporters had hinted to New York, the statue’s promised location, that Lady Liberty would be just as welcome in Philadelphia should New Yorkers fail to do their part. In October, The New York Times fired back with an outraged editorial, accusing Philadelphians of setting their "piratical hearts" on "other people’s lighthouses."

Still, there was no denying that the pedestal would be expensive. Building the base alone would cost $250,000, and Americans couldn’t justify spending that much on a "Frenchy and fanciful" statue. If it was a gift, why didn’t France just throw in the pedestal too? The American Committee and other supporters refused to give up. They appealed to everyone from schoolchildren to Civil War veterans. President Ulysses S. Grant and Theodore Roosevelt chimed in with support. But it took the curmudgeonly owner of theNew York World newspaper to finish the job.

"We must raise the money!" Joseph Pulitzer boomed in an editorial, announcing that his paper would run a subscription campaign to raise the $100,000. Within five months, 120,000 people responded to his appeal. Some donated as much as $2,500; most contributed what they could, often less than a dollar. By August 11, 1885, the pedestal campaign had reached its goal. With the funding under control, there was an even bigger challenge to surmount: No one had ever attempted to build a statue so large.

Building Lady Liberty

The description of how Lady Liberty was built reads like a word problem. Bartholdi’s workmen started by creating a 4-foot model. Then they doubled the size. Then they quadrupled it to create a 38-foot-tall plaster model. The workmen then broke down the structure into 300 sections, taking each piece and enlarging it to precisely four times its size. The result? A full-scale model of the final statue-in pieces! Next, the workmen used the pieces to create a mold using either wood or malleable lead sheets depending on the shape; and finally, they hammered the copper sheets against the shape. Though the finished statue is solid, each one of the 310 copper sheets that make up her skin is incredibly thin: the width of just two pennies stuck together.

But Bartholdi still needed help with the structure, so he recruited another famous Frenchman, Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel. At the time, Eiffel was known simply as a bridge engineer; ground wouldn’t be broken on the tower that bears his name for another decade. But he had a reputation for innovation. Eiffel started by creating a flexible iron skeleton. The frame had enough give for the copper to expand in the sun’s heat-otherwise the statue’s skin would buckle and crack. He also used his knowledge of the pressures on bridges and viaducts to great effect, ensuring that the structure would bend with the wind, thanks to a framework of trussed iron pylons off a central pillar. In fact, Eiffel’s design for the structure anticipated the principles that would later make the great 20th-century skyscrapers possible.

But Bartholdi still needed help with the structure, so he recruited another famous Frenchman, Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel. At the time, Eiffel was known simply as a bridge engineer; ground wouldn’t be broken on the tower that bears his name for another decade. But he had a reputation for innovation. Eiffel started by creating a flexible iron skeleton. The frame had enough give for the copper to expand in the sun’s heat-otherwise the statue’s skin would buckle and crack. He also used his knowledge of the pressures on bridges and viaducts to great effect, ensuring that the structure would bend with the wind, thanks to a framework of trussed iron pylons off a central pillar. In fact, Eiffel’s design for the structure anticipated the principles that would later make the great 20th-century skyscrapers possible.

For his part, Eiffel wasn’t impressed by his own genius, and he rarely talked about the statue. When he did, it was mostly about the structure: "The work has well resisted the formidable storms that have assailed it."

Fashionably Late

The Statue of Liberty was nearly a decade late to her own party. By the time she was completed in July 1884, Bartholdi had spent 19 years on the project. Laboulaye had died the year before. For half a year, Liberty stood completely assembled in Paris’s 17th arrondissement, waiting to catch a ride to America. When she finally did, she was disassembled into 350 pieces and packed in 214 boxes.

It took 26 days on a frigate to reach Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor, her new home. The pedestal wasn’t completed until April 1886. It took another four months to reassemble her skeleton and rivet on Lady Liberty’s pre-patina skin, which was still a deep, ruddy brown. And because the pedestal was so small, no scaffolding could be erected around her! Workers dangled from ropes latched to the framework, buffeted by the harbor winds.

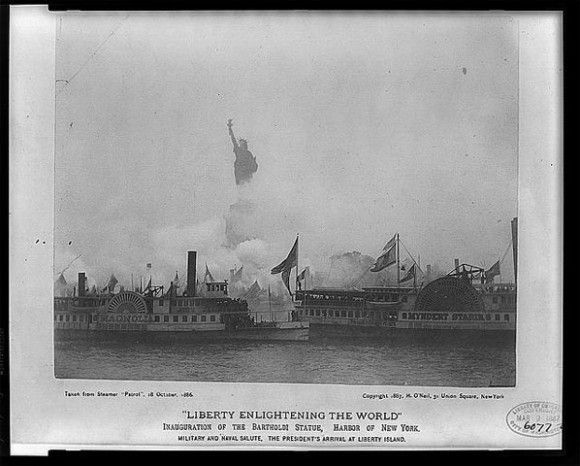

On October 28, 1886, the Statue of Liberty was finally ready. New York held its first-ever ticker tape parade for her unveiling. And while hundreds of thousands cheered from Manhattan, only 2,000 people were on the island when she was finally opened to the public-a "tidy, quiet crowd," an officer on duty told The New York Times.

Since then, the now pastel-green goddess has risen above New York Harbor, her torch welcoming the "huddled masses" to America. The world knows her as the everlasting symbol of justice, opportunity, and freedom against tyranny. And though fewer are aware of it, she is also the symbol of France’s own hopes for democracy, an example of the impressive fundraising power of two countries and, above all, a reminder of the worst gift-giving etiquette in recorded history.

_______________________

The article above, written by Linda Rodriguez McRobbie, is reprinted with permission from the March-April 2013 issue of mental_floss magazine. Get a subscription to mental_floss and never miss an issue!

The article above, written by Linda Rodriguez McRobbie, is reprinted with permission from the March-April 2013 issue of mental_floss magazine. Get a subscription to mental_floss and never miss an issue!

Be sure to visit mental_floss' website and blog for more fun stuff! ![]()

See "She Was Never About Those Huddled Masses," by Roberto Suro, founding director of the Pew Hispanic Center (and now director of the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute at USC) in the WaPo at Independence Day, 2009: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/02/AR2009070201737_pf.html

The statue is not, in any way, an "argument" in favor of immigration, but a lot of ignorant people think it is.