The following article is from the book Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV.

The following article is from the book Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV.

On a spring day in 1920 in Rigby, Idaho, a farm boy named Philo took a break from his plowing and invented television. Then his amazing invention was stolen from him.

ALONE IN HIS FIELD

Electricity and radio in 1920 were like computers in the 1970s: exciting new innovations into which the technologically minded put their dreams, mental energy, and considerable spare time. Fourteen-year-old Philo Taylor Farnsworth -tall, skinny, and full of ideas- was already showing promise as an electricity prodigy. Two years earlier, shortly after he'd seen an electric light for the first time, he'd re-wired a burned out motor and presented his family with its first automatic washing machine.

Living on a farm meant lots of tedious chores, which gave Philo plenty of time to think. As he was plowing a field one day, he started wondering if it was possible for radios to broadcast moving pictures as well as sound.

SPINNING THE WHEELS Philo certainly wasn't the first person to come up with the idea of sending images over the air. He'd found a stack of science magazines in the attic (they were there when his family moved in), with articles about European experimenters trying to do just that. One of the more promising attempts: German inventor Paul Nipkow had rigged a spinning wheel mounted on a lit picture, dotted with tiny pinholes. As the hand-cranked wheel spun rapidly in front of a brightly-lit scene, the first pinhole let in a thin strip of light from the top of the scene, the next let in another thin strip, and so on- thus the entire scene was rapidly scanned from top to bottom over and over again.

Philo certainly wasn't the first person to come up with the idea of sending images over the air. He'd found a stack of science magazines in the attic (they were there when his family moved in), with articles about European experimenters trying to do just that. One of the more promising attempts: German inventor Paul Nipkow had rigged a spinning wheel mounted on a lit picture, dotted with tiny pinholes. As the hand-cranked wheel spun rapidly in front of a brightly-lit scene, the first pinhole let in a thin strip of light from the top of the scene, the next let in another thin strip, and so on- thus the entire scene was rapidly scanned from top to bottom over and over again.

How did that make TV? The thin strips of light landed on photosensitive material that generated a little surge of electricity when the light hit it. The brighter the light, the more juice was produced; connected electrically to that wheel was another wheel spinning at exactly the same rate of speed while transforming the electric signals back into light again. Demonstrations showed promise: Images, while ill-defined, could be recognized and transmitted.

PLOWING AHEAD

Philo thought about the spinning wheel device as he plowed. He felt it was a great idea but knew it would never lead to broadcasting images. First of all, the two wheels would have to spin at exactly the same rate all the time, or the images would be lost. That can easily be managed if the wheels are a few feet apart in a laboratory, but how do you maintain the same speed if the wheels are hundreds of miles apart, the transmitter in one place and the receiver in a home? And if it was used in large-scale broadcasting, every wheel on every receiver would have to be synchronized -a near-impossible feat.

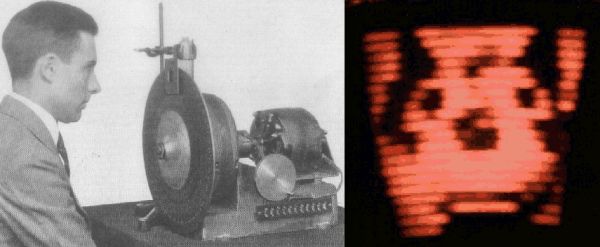

A man watching mechanical TV. At right, a 1928 image of Felix the Cat broadcast mechanically.

A man watching mechanical TV. At right, a 1928 image of Felix the Cat broadcast mechanically.

Philo knew there had to be a better approach, one that wouldn't require wheels or mass synchronization. That's when, according to legend, he stopped plowing and looked around -his plow had created equally spaced parallel lines all over the entire field. He'd read that scientists could manipulate the motion of an electron thousands of time per second in a vacuum tube, so he looked at the field and saw a large vacuum tube acting as a screen. And "plowing" that field was a thin ray of light, pulled by alternating magnetic fields, moving across the screen in superfast "furrows" while lighting up selected pieces along each furrow. Phil realized that if this were done in a fraction of a second and repeated, the human eye would perceive motion.

Over the next few months, Philo thought about his vision some more and realized that if he scanned the picture electronically instead of mechanically, he could add more speed and more high-definition scan lines (the "furrows") -maybe 30 frames a second and 500 lines that European researchers like Nipkow had obtained.

SHOW ME THE MONEY Farnsworth continued to research and refine his ideas in his spare time, eventually enrolling in Brigham Young University at age 17. He had access to laboratories and like-minded students, but the problem was funding. Nobody wanted to blow money on the fantastical invention of a self-taught farm boy trying to outdo some of the greatest scientists of Europe.

Farnsworth continued to research and refine his ideas in his spare time, eventually enrolling in Brigham Young University at age 17. He had access to laboratories and like-minded students, but the problem was funding. Nobody wanted to blow money on the fantastical invention of a self-taught farm boy trying to outdo some of the greatest scientists of Europe.

His luck changed when he joined the Community Chest, a charity group at BYU. A couple of the organization's directors were philanthropists from California, and one of Farnsworth's friends told them about his ideas. To his surprise, they agreed to provide modest funding to set him up in California. Farnsworth moved west and rented a 30-by-30-foot lab in San Francisco. He had just turned 19 years old.

Farnsworth and a small staff diligently experimented with electricity, vacuum tubes, and electrons in the lab for three years. His backers became impatient, having yet to receive a return on the $1,000 a month it cost to keep the research afloat. Finally, in late 1927, Farnsworth's team projected a line of light into a camera behind a photographic slide, and sent it to a screen. Seven months later, in May 1928, Farnsworth presented more than a line of light -he transmitted an image. Fittingly enough, it was a dollar sign.

SMEAR TACTICS

When word got out that a guy working on his own in San Francisco accomplished a system for broadcasting and receiving images with electric signals, one man saw red: David Sarnoff, an executive with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), in charge of NBC Radio, the company's emerging radio network and TV development. Sarnoff had been trying the same thing, spending years and millions of dollars on a staff of 60, headed by inventor Vladimir Zworykin. While working with RCA, Zworykin had applied for a patent in 1923 for a rudimentary electronic television system but had been turned down by the patent office because there was no evidence that he could produce a working device. He tried again in 1925 with some changes, including a way of producing color, and was eventually awarded a patent in 1928 for the technology, even though it didn't actually work. It was at that time that Farnsworth's developments went public.

Under Sarnoff's direction, RCA amassed a busy staff of patent lawyers who sued anybody stepping on what they considered their turf. They had hounded and financially ruined several inventor who wouldn't sell out to them; they figured they would make similar short work of young Farnsworth.

BATTLE OF THE STARS When Farnsworth was granted a patent in his television system in 1928, Sarnoff declared war. RCA launched a publicity campaign lauding Zworykin as the "true father" of the coming television age and sent employees to harass Farnsworth when he made public appearances. It worked -potential licensors of the technology were confused about who actually held the rights.

When Farnsworth was granted a patent in his television system in 1928, Sarnoff declared war. RCA launched a publicity campaign lauding Zworykin as the "true father" of the coming television age and sent employees to harass Farnsworth when he made public appearances. It worked -potential licensors of the technology were confused about who actually held the rights.

Eventually, RCA's actions goaded Farnsworth into filing a patent clarification suit, an expensive proposition in which he would have to prove to a judge that his inventions (and the documentation of them) had come first. RCA also sued Farnsworth for patent infringement based on the application Zworykin had made in 1923 for his own original, unworkable system.

PHILO'S DOUGH

Farnsworth fought back -he hired excellent patent attorneys that he couldn't afford, hoping to recoup his losses from licensing when his patent was cleared. To raise money, he went overseas and sold the rights to his patents in England and Germany, where RCA couldn't easily interfere. (Cameras developed by Farnsworth broadcast the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.) Farnsworth's lawyers tracked down witnesses to back up his claims, including the science teacher he had run his ideas past in high school.

The testimony of science teacher Justin Tolman was enough to demolish RCA's patent infringement claim. After describing his conversation with the teenage Farnsworth, he pulled out a rumpled, yellow piece of paper out of his coat pocket and explained, "This was made for me by Philo in early 1922." The drawing showed Farnsworth's idea for his "Image Dissector" camera, drawn more than a year before Zworykin had applied for his patent.

Recreation of Farnsworth's original sketch for his science teacher.

Recreation of Farnsworth's original sketch for his science teacher.

The court ruled for Farnsworth. He now had six clear patents and licensing rights to collect payment from any company -including RCA- that wanted to make television equipment based on them.

PLAYING DIRTY

RCA was determined to exact vengeance. While quietly negotiating the rights to use Farnsworth's patents, eventually agreeing to pay a million dollars up front and a royalty in every RCA receiver sold, the company embarked on a publicity blitz. Most notably, President Franklin Roosevelt appeared at their pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair in New York City. The event was aired to the handful of TV sets in existence at the time -one of the first-ever widespread broadcasts. Sarnoff gave a bold speech announcing RCA's intention to begin regular TV programming, and claimed the company had developed the technology itself.

Sarnoff at the World's Fair.

Sarnoff at the World's Fair.

The press took him at his word and trumpeted RCA's "breakthrough" across the land. It was the first step in a long campaign to erase Farnsworth's name from the history of television, successfully replacing it with the names of Sarnoff and Zworykin. It worked so well that even now, with the record finally set straight and even a postage stamp honoring Farnsworth, some sources still mistakenly list Zworykin as the "inventor of television."

By the time Farnsworth had definitely established his claims to his patents, it was 1939. However, the patents had been granted in 1928 and, since patents lasted for only 17 years at that point, his time to profit from his invention was more than half over. He was still deep in debt and ready make some money. Television manufacturers were lining up to make deals. In a few more years, he expected that that he would be not just solvent but fabulously wealthy.

BLITZKRIEG FLOP Then something happened that was even bigger and more financially disastrous than RCA's campaign: World War II. In 1941 -year 13 of Farnsworth's 17-year patents- the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. When the United States entered the war, the government shut down the manufacture of "nonessential" products, especially those whose components and engineers were needed for the war effort. Like televisions.

Then something happened that was even bigger and more financially disastrous than RCA's campaign: World War II. In 1941 -year 13 of Farnsworth's 17-year patents- the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. When the United States entered the war, the government shut down the manufacture of "nonessential" products, especially those whose components and engineers were needed for the war effort. Like televisions.

As it sunk in to Farnsworth that his invention could never pay out, he went into a deep depression -he drank, stopped eating, and shrank to 100 pounds. It didn't help that Sarnoff convinced the Radio Television Manufacturers Association to honor him as "the father of television" and instructed his employees to always add "The Inventor of Television" to any public mentions of Zworykin.

MOVING FORWARD

The war ended in 1945, and TV manufacturing and development resumed, but Farnsworth's patents had expired. Adding insult to injury was what he saw being broadcast. Farnsworth had cherished a belief that his invention would lead to widespread education, culture, and understanding of other people. Instead it featured commercials for cars, headache remedies, and beer, sandwiched between soap operas, game shows, and wrestling matches.

With the help of his family and new ideas for inventions, Farnsworth eventually regained his emotional equilibrium. He went on to hold almost 300 patents on products as diverse as a baby incubator, a gastroscope, an electron microscope, and even a small nuclear fusion device.

INTO THE FUTURE

Finally, two years before he died, Farnsworth was able to experience a father's pride as his ne'er-do-well child lived up to everything he hoped. On July 20, 1969, the inventor joined much of the world in watching a live broadcast as astronauts stepped onto the moon for the very first time. When it was over, he turned to his wife and said, "This has made it all worthwhile."

Years of disappointment had soured Farnsworth on television, and he rarely watched it before his death in 1971. However, he did appear on TV twice. Once was an interview at the local station in Rigby, Idaho, near where he had invented TV as a boy. The other was as the mystery guest "Dr. X" on I've Got A Secret, in which celebrity contestants attempted to guess his accomplishment using only yes-or-no questions. When the panel couldn't guess his secret, he won $80 and a carton of Winston cigarettes.

___________________

The article above was reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV. Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts.

The article above was reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader Tunes Into TV. Since 1988, the Bathroom Reader Institute had published a series of popular books containing irresistible bits of trivia and obscure yet fascinating facts.

If you like Neatorama, you'll love the Bathroom Reader Institute's books - go ahead and check 'em out!

Also, there is a reason the professor on Futurama is named Prof. Farnsworth...